Cave Women Were Artists Too

A close-up of one of the 30 hand stencils from El Castillo.

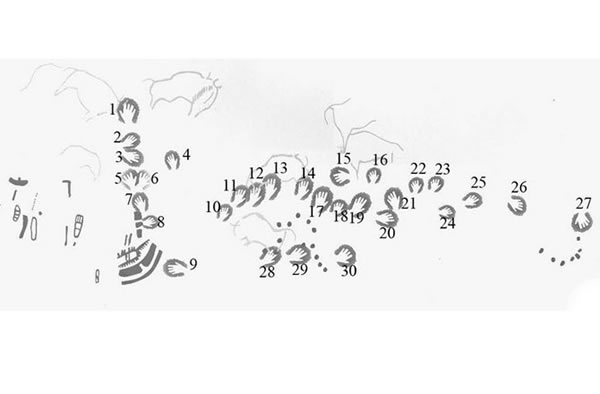

A diagram of Stone-age handprints found on Friso de Las Manos, El Castillo, Spain.

Stone-age hand prints on the walls of Spanish and French caves have long been assumed to be those of men and adolescent boys, but new research shows they are mostly those of women.

The discovery starts with the work of British physician John Manning who gathered hand and digit measurements of patients to see if there were significant differences between men and women, as well as people from different populations in other parts of the world.

That research of more than a decade ago showed there were, indeed, differences in digit ratio lengths between men and women -- what's called sexual dimorphism -- although about a significant fraction of the modern hands overlap and can't be so easily distinguished by gender.

"They published a popular book about digit ratios," said anthropologist Dean Snow of Pennsylvania State University, the author of a paper in the current issue of American Antiquities about the cave hand prints. "That's when I stumbled on it. I thought surely someone had used this in the archaeological community. But I was surprised to find that nobody had done this in connection to the rock art."

So that's what he did, visiting caves in Spain and France to measure and photograph ancient hand prints and stencils (the first being made with hands dipped in paint then pressed against the cave wall and the second being made by spit-spraying paint on the hand pressed against the wall to make an outline).

"The first surprise was that it wasn't half and half," said Snow, regarding the gender of the hands represented in Spanish and French caves.

On the contrary, fully 75 percent of the hand prints he studied appear to be those of women. Only 10 percent were clearly those of adult men and 15 percent are probably those of adolescent boys. If anything, the sexual dimorphism in hands of those early southern Europeans was more pronounced than it is today, he said.

"I've used the same criteria to assess stencils in El Castillo and La Garma caves (both in Cantabria), said archeologist Paul Pettitt of Durham University in the UK, "and I would say that my unpublished data are consistent with the notion that stencils are of the hands of adult females."

Pettitt also cautions against jumping to too many conclusions about Snow's discovery.

"It may or may not be justified to assume that these females were the individuals who created the stencils," Pettitt explained. "We should distinguish between the stenciled and the stenciler. To play devil's advocate, how could we eliminate the hypothesis that it is male/female pairs who create stencils, the male stenciling the female?"

Secondly, Pettitt points out that the hand prints do not automatically imply that all cave art was done by women. In fact there is growing evidence that hand stencils and the more figurative art in the caves were done at very different times by entirely different people.

"It's been pointed out before that when we think of 'cave artists' we unconsciously think of bearded male hunters," said Pettitt. "Snow's work admirably reveals that adult females were being immortalized on cave walls."

Snow has also attempted to apply the same techniques to ancient hand prints in North America, but without success. Those will probably require an entirely different analysis.(Oct 16, 2013 02:10 PM ET // by Larry O'Hanlon)