NASA's Next Mars Rover to Search for Past Life

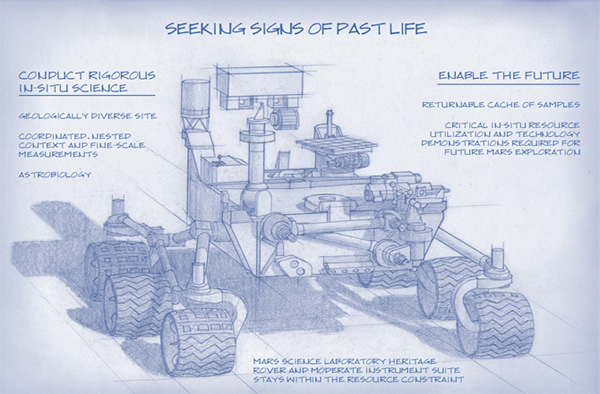

A sketch of the design for NASA's 2020 Mars rover.

NASA’s follow-on Mars rover should not only look for signs of past life, but also prepare samples for an eventual return to Earth, a science advisory team said Tuesday.

The mission, called Mars 2020, would build on evidence already collected by NASA’s Curiosity rover that the planet most like Earth in the solar system had at some point in its past all the ingredients and suitable environments to support microbial life.

Curiosity touched down in August 2012 inside an ancient impact basin called Gale Crater and hit pay dirt in its first detailed analysis of a piece of once water-soaked bedrock.

From that sample, scientists could not pin down exactly when the chemistry for life existed on Mars, but they hope to learn more when Curiosity analyzes rocks in and around Mount Sharp, a three-mile-high mound of layered sediment rising from the crater’s floor, which is the primary target for the two-year mission.

Mars 2020, which as the name implies will launch in 2020, would duplicate Curiosity’s chassis and sky-crane landing system, but swap out its science instruments with new tools that would, in effect, put Mars under a microscope.

“Such observations are especially valuable for interpreting unusual small-scale features and patterns in rocks, which is essential to the search for bio-signatures,” the scientists wrote in their report.

In addition to on-site analysis, the rover would collect and seal about 31 samples into a container for an eventual return to Earth, the advisory group said.

“Perhaps human explorers will go and retrieve the cache in 20-plus years from now. That’s an eventual goal is to put astrobiologists and planetary scientists on the surface of Mars,” John Grunsfeld, a former astronaut who now serves as NASA’s associate administrator for science, told reporters on a conference call.

NASA plans to study the group’s report before issuing a solicitation for science instruments for the new rover.

The project, which would cost about $1.5 billion not including a launch vehicle, follows a proposed life-detection mission overseen by the European Space Agency that is expected to launch in 2018. Unlike Europe’s ExoMars, the NASA rover would not drill deeply into the Martian terrain to search for ancient life and life-friendly habitats.

Rather, the U.S. mission likely would rely on an enhanced landing system to set the rover down in a relatively fresh crater. Scientists believe that a recently excavated section of Mars might still have preserved organic material despite being exposed to the harsh radioactive surface environment.(Jul 9, 2013 04:45 PM ET // by Irene Klotz)