In Kulluk’s Wake, Deeper Debate Roils on Arctic Drilling

Shell's Kulluk ran aground off the southern coast of Alaska in a violent storm. The rig was towed to safe harbor, with no apparent release of fuel aboard, but the accident could have wide repercussions for Arctic drilling.

Part of our weekly "In Focus" series—stepping back, looking closer.

When the energy company Shell* was allowed the first crack in decades at drilling for oil in promising patches of the Arctic off the coast of Alaska, it didn’t skimp, energy analysts say. The company deployed the Kulluk, a rig designed to withstand the rigors of drilling in the Beaufort Sea. And it deployed a brand-new ship to tow the Kulluk to Seattle for maintenance after the drilling season was over.

Even so, Shell’s careful preparations ended with a technological and PR disaster: the grounding of the Kulluk in a storm on the rocky shoreline of southern Alaska on New Year’s Eve, after the new ship lost all four engines and the Kulluk broke free.

The Kulluk story is a cautionary tale for the crowd of energy companies looking north. An oil rush has hit the Arctic, as companies run out of other places to drill and shrinking sea ice leaves more open water. From Alaska’s northern seas to the frigid waters off Siberia, companies are pumping billions of dollars into exploration and new infrastructure in the hope that they’ll be able to pump oil and gas worth even more from the icy depths.

But the Kulluk incident shows that not even the sharpest minds know exactly how to drain the oil beneath the northernmost Arctic, an area that is among Earth’s most extreme environments. And even meticulous plans years in the making can end in embarrassing failure—or worse.

Risky Business

Prospecting in Arctic waters “is a very risky business, no matter how you slice it,” said Lysle Brinker of Colorado-based IHS CERA, an energy research and analysis firm. “They’re pushing . . . into waters and exploration frontiers that are for the most part uncharted, untested.”

“The size of the prize is very large, and it is up for grabs,” said Surya Rajan, also of IHS CERA. “But we just can’t figure out a good way to get at it.”

The Kulluk accident, now the subject of a review ordered by U.S. Interior Secretary Ken Salazar, may force Shell to abandon its plans to look for oil and gas off Alaska this summer, and repercussions of the mishap could extend to other energy companies as well. The incident has reinforced concerns that drilling could lead to an Arctic version of the catastrophic Deepwater Horizon spill in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010. (Related Quiz: “How Much Do You Know About the Gulf Oil Spill?”) Other companies, which are keeping a close eye on Shell’s plight, may decide to delay their campaigns to search for oil and gas in the Arctic, Rajan said.

The stereotypical image of an oil well is a rig amidst the sands of the Saudi desert or the waves of the sultry Gulf of Mexico. But a 2008 report by the U.S. Geological Survey estimated that the area north of the Arctic Circle holds 13 percent of the world’s undiscovered oil, the main ingredient in gasoline and other fuels, and 30 percent of its undiscovered natural gas, used for heating and for producing electricity. Nearly 85 percent of those resources, the report said, lie not on land but under frigid Arctic waters.

Energy companies have been extracting oil and gas from the far north for decades, mostly in the subarctic. But now interest in the Arctic is growing—even in the iciest locales, said Edward Richardson, an associate analyst at London-based Infield Systems, an energy research firm.

Forging Ahead

Russia’s first Arctic oil field could start producing oil later this year, he says. Exxon Mobil signed a deal in 2012 to prospect for oil and gas in Russia’s ice-laden Kara Sea. Despite Shell’s troubles, ConocoPhillips plans to drill one or two exploratory wells in the Chukchi Sea e in 2014, a spokesman said.

Why would companies brave the ice, the cold, the lack of hotels and golf courses to drill in such isolated locales? Experts say the big energy firms are out of options. Existing megafields, such as those in Alaska’s North Slope, are running dry, and many countries with massive oil and gas deposits have chased private companies off.

“These big companies don’t really have a lot of choice but to go up there,” said Charles Ebinger, an energy analyst at the Brookings Institution in Washington, D.C.. “They almost have to.”

Fortunately for the energy industry, the Arctic has become more hospitable to drilling just as other locations have become more hostile. The Arctic sea ice melted away to a record low in 2012, according to the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, spelling easier access for drill ships, though melting ice also brings new problems.

Technological innovation has also given industry a freer hand. Companies have learned to bury pipelines to protect them from ice that scours the seafloor. Drill ships that can operate in deeper water and drill to greater depths are being designed.

Even so, it will be perhaps a decade before large quantities of oil begin to gush from the iciest parts of the Arctic. Engineers have to figure out how to supply power to equipment below the ice, and how to keep their products flowing through pipelines in extreme temperatures. In Alaska, there’s no port within hundreds of miles of the Chukchi that could host large support or emergency-response ships.

“I’m convinced it can be done right,” Ebinger says, referring to oil production in the northernmost Arctic. “But as we’ve seen with this recent incident . . . no one should underestimate the difficulty of drilling in conditions like that.”

The Kulluk wasn’t even in Arctic waters when it broke free of its tow ship. Instead the rig was in the more hospitable shipping lanes off southern Alaska when a violent storm caused it to lose its mooring to tow ships and run aground, leading to a U.S. Coast Guard-coordinated rescue and recovery operation that involved more than 700 people.

So far there doesn’t appear to have been any breach of the Kulluk’s steel tanks holding 150,000 gallons of diesel fuel and oil products, although officials say some fuel may have spilled from rescue ships that dislodged from the rig when it was grounded.

Shell’s other drill rig, the ship Noble Discoverer, hasn’t avoided mishap, either. In mid-July, before heading north, it slipped its anchor in Alaska’s Dutch Harbor and drifted perilously close to shore. It had to halt its drilling campaign on the Chukchi Sea to dodge a 30-mile-long (48-kilometer-long) ice floe. After it returned to harbor in the fall, a small fire broke out aboard the ship.

Shell has stressed that the Kulluk incident was a transportation accident, and did not involve drilling, nor was there any risk of crude oil release. The company has pledged to cooperate in the investigation into the causes of the incident and to implement lessons learned.

“We undertake significant planning and preparation in an effort to ensure these types of incidents do not occur,” said Marvin Odum, president of Shell Oil Company, in a statement. “We’re very sorry it did.”

But critics point to the Kulluk episode as evidence that—despite the promises of Shell and other companies—too little has been done to ensure that drilling doesn’t damage the fragile Arctic environment..

Every time new drilling is proposed, “invariably the proponents swear up and down that this time will be different, that they’re going to apply the very best technology, the very tightest standards,” said environmental chemist Jeffrey Short, a former staffer at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration who is now a consultant for the U.S. environmental group Oceana. “That doesn’t offer much comfort once an accident happens.”

At the moment, he said, there’s so little monitoring of offshore weather and currents that “if a spill occurred, you’d just be flying blind as far as being able to anticipate where to look for the oil.”

Nightmare Scenario

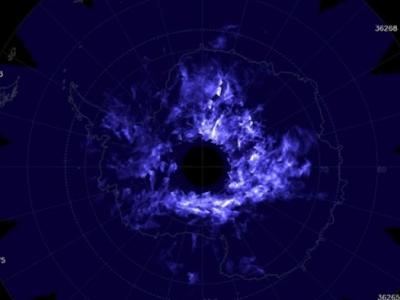

An Arctic “blowout”—an uncontrolled leak triggering an the immense oil flow like the one that happened during the Deepwater Horizon disaster—could create a trail of oil-tainted ice nearly 2,000 miles (3,000 kilometers) long, said University of Cambridge ocean physicist Peter Wadhams, who studies polar ice. That nightmare scenario could become reality if an oil well were leaking when winter ice began to form. Ice near the spill would absorb oil and then drift away, allowing a fresh expanse of ice to soak up oil. There is no way to clean up oil that’s under or in ice, Wadhams said, though it’s possible a method could be developed.

Though the Arctic seems barren, the region nourishes large numbers of birds, walruses, seals, and whales, some of them increasingly rare.

The Arctic is full of “species that are slowly but surely all being put on the endangered species list,” said Marilyn Heiman, a former U.S. Interior Department staffer who now heads Arctic protection efforts for the non-profit Pew Environment Group. “If there’s an oil spill it will be a disaster.”

And not just for animals. The Inupiat Eskimos living on Alaska’s northern coast depend on the sea for food but also as a stage for traditions, such as the bowhead-whale hunt, that are central to their culture.

“We refer to the ocean as our garden, because that’s where we get our seals and walruses. We don’t have Safeway,” said Inupiat elder and politician Edward Itta, who is resigned to drilling in the Arctic but has pushed for stricter regulations. “If the bowhead whale is no more, that in essence would shut down our way of life.”

Stricter safety standards could help reduce the risk of a catastrophic Arctic oil spill, Heiman said, but “this is the most dangerous place in the world to operate . . . . It’s going to be high risk, no matter what.”

*Shell is sponsor of National Geographic’s Great Energy Challenge initiative. National Geographic maintains autonomy over content.

Traci Watson

National Geographic News