Sky-watchers Get Set for Cosmic Fireworks Show

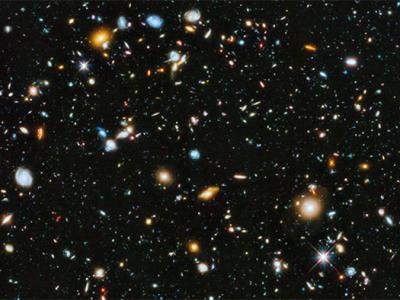

A shooting star—part of the Geminid meteor shower—lights up California's night.

Sky-watchers are in for an early holiday treat as mid-December marks the peak of the Geminid meteor shower, the most prolific and mysterious annual cosmic fireworks show.

The meteor shower has been growing in intensity in recent decades and should be better than usual this year because it falls during a nearly moonless week.

Dozens of shooting stars per hour should streak across the night sky on the night of December 13 and into the early hours of December 14, making the Geminids one of the strongest and most reliable celestial shows around.

"Usual estimates of yield are between 80 and 120 meteors per hour—under good viewing conditions," said Ben Burress, staff astronomer at the Chabot Space & Science Center in Oakland, California.

"Fortunately December 13th is [a] new moon, so there will be no moon at all during the shower," Burress added. He emphasized that viewing from as dark a location as possible, far from city lights, is the best way to see the meteors.

Stronger Through the Years

Historically the Geminids were overlooked by most amateur astronomers simply because the annual event occurs so close to the busy holiday season and frigid winter nights—but that's beginning to change thanks to its rising intensity over the past few decades.

In fact, for many astronomers, the December meteors have now dethroned the more popular August Perseids as the shooting-star event of the year.

"This shower was first noticed in 1862, and its intensity has been increasing over the past hundred years," said Jim Todd, planetarium manager at the Oregon Museum of Science and Industry.

"Around the year 1900, the peak averaged 15 to 20 meteors per hour, but it is now grown to well over a hundred per hour," Todd said.

Mysterious Parentage

The reason for the upswing? Astronomers believe that Earth is plowing deeper every year into an ancient debris stream left behind by a mysterious three-mile-wide (five-kilometer-wide) asteroid-like object orbiting the inner solar system.

But unlike other meteor showers that spring from material shed from melting icy comets as they swing close to the sun, scientists aren't sure whether the Geminids' parent object, called 3200 Phaethon, is an asteroid or a nearly dead comet.

"The object does not develop a cometary tail when it passes near the sun, but bits of it do break off during its journey past the sun," Todd explained. "When Earth passes through this debris, we experience the Geminid meteor shower," he said.

After Phaethon was discovered in 1983 by a NASA satellite, astronomers quickly matched its year-and-a-half orbit precisely with the Geminids, making it a prime candidate for the source of the meteors.

A Great Show

Since Geminids hit the atmosphere at about 20 miles per second (32 kilometers per second)—slower than other meteor showers—they create beautiful long arcs across the sky that can last for a second or two.

Favoring observers in the Northern Hemisphere, the shower's radiant—the point in the sky from which the meteors appear to originate—is the constellation Gemini, which rises above the eastern horizon after 9 p.m. local time.

Observers will want to head outside between 10 p.m. and 5 a.m. local time, said Burress, but the best views will be in the wee hours of Friday morning.

"At around 2 a.m. local time is the when the show will be at its best—as the shower's radiant point in Gemini reaches highest in the sky, directly south," he advised.

And for a sky-watching bonus, Todd points out that keen-eyed observers will also have an opportunity to spy several planetary neighbors as shootings stars rain down.

"Just west of the constellation Gemini will be the brilliant planet Jupiter shining bright, visible throughout the night," Todd said. "While just before sunrise, Saturn, Venus, and Mercury appear above the southeastern horizon for a beautiful display."

"Get yourself a blanket and a clear view of the sky, because you could be in for a great show."

Andrew Fazekas

for National Geographic News

Published December 11, 2012