Pulsating Aurorae Secrets Revealed

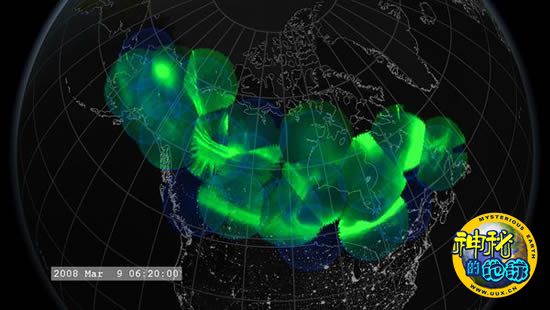

Aurorae are seen in a satellite image from NASA's THEMIS.

Andrew Fazekas

for National Geographic News

Published October 1, 2010

The ghostly glows of the northern lights have awestruck generations of sky-watchers. But the inner clockwork behind the most intense displays has remained a mystery—until now.

Scientists have found the elusive trigger that sets off the most striking visual outbursts, known as pulsating aurorae or blinking lights around Earth's polar regions. (See aurorae pictures.)

Though typical auroras usually stretch more than 620 miles (a thousand kilometers), and last only minutes at a time, pulsating aurora are small glowing patches of light about a 62 miles (a hundred kilometers) wide that flash on and off every 5 to 40 seconds. This flickering gives the appearance of exploding lights in the sky.

"The driver behind auroral pulsation has been a long-standing question in the auroral physics community for more than four decades," said project leader Toshi Nishimura, a researcher at University of California, Los Angeles.

But Nishimura and colleagues discovered the driving force behind the unusual cosmic fireworks appears to be a particular type of electromagnetic wave that originates in Earth's protective, bubble-like magnetosphere.

Solar Wind Collisions Create Bursts of Light

When solar wind—a stream of charged particles released from the sun—strikes our planet's magnetic field, the wind gets funneled down into the atmosphere.

(Related: "Surprise: Solar System 'Force Field' Shrinks Fast.")

The charged particles collide with atmospheric molecules and sometimes form bursts of light known as chorus waves.

Nishimura and his team were able to make their discovery thanks to a fleet of 20 ground-based, all- sky imagers scattered across northern Canada and Alaska. The fleet is part of the Canadian Space Agency and NASA's THEMIS mission, which also includes five low, Earth-orbiting satellites.

On the night of February 15, 2009, the team hit the jackpot when one of the ground cameras picked up a pulsating display that was simultaneously correlated to a chorus wave detected by one of the THEMIS satellites above the display's location.

"This high correlation between the intensities of chorus and aurora was quite remarkable for us," Nishimura said.

(Related aurora pictures: "Sky Shows Sparked by Sun Eruption.")

Armed with this new data, Nishimura said, physicists should now be able to hone their magnetic field models with much higher accuracy.