"Lucy" Kin Pushes Back Evolution of Upright Walking?

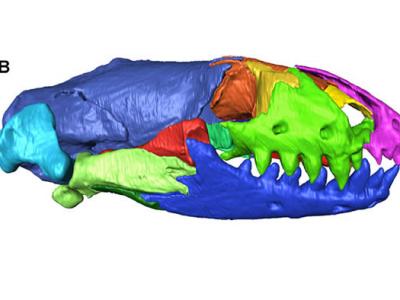

"Lucy," a 3.2-million-year-old human ancestor, is seen in an artist's rendering.

Ker Than

for National Geographic News

Published June 21, 2010

A newfound male relative of the human ancestor "Lucy" supports the idea that walking upright evolved earlier than thought, a new study says.

Lucy—a 3.2-million-year-old skeleton discovered in 1974—belongs to Australopithecus afarensis, a species which scientists think was an early direct ancestor of modern humans.

An exceptionally petite female—her estimated height was 3.5 feet (1.1 meters)—Lucy's small frame has been interpreted as not being totally adapted for human-like, upright walking.

(See: "6-Million-Year-Old Human Ancestor 1st to Walk Upright?")

But the discovery of the 3.6-million-year-old male disproves that idea, said study co-author Yohannes Haile-Selassie, curator of physical anthropology at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History.

"As a result of this discovery, we can now confidently say that 'Lucy' and her relatives were almost as proficient as we are walking on two legs, and that the elongation of our legs came earlier in our evolution than previously thought," Haile-Selassie said in a statement.

"Big Man" A. Afarensis Fossil Similar to Humans

Scientists nicknamed the new A. afarensis fossil "Kadanuumuu," which means "big man" in the Afar language of central Ethiopia, where the fossil was found in 2005.

The name refers to the fossil's height, which scientists estimate is between 5 and 5.5 feet (1.5 and 1.8 meters) tall.

In addition to being much bigger than Lucy, the new fossil contains a more complete shoulder blade than previously known, a major portion of the rib cage, and pelvis fragments that shed new light on how A. afarensis moved.

Kadanuumuu's skeletal features are surprisingly similar to those of modern humans, Haile-Selassie said in an interview.

This supports recent findings that suggest chimpanzees are not good models for the study of our early human ancestors, he added. (See a map of where human ancestors are found around the world.)

For example, the team also argues that Kadanuumuu's shoulder bone, or scapula, is much less ape-like than previously thought based on Lucy's small shoulder bone fragment.

"Until now, most scientists presumed that our ancestors' shoulders were more like those of chimpanzees," Haile-Selassie said.

Based on their preliminary analysis of the male fossil's scapula, the team argues A. afarensis was no better or worse at tree climbing than modern humans.

"Its anatomy wouldn't allow it to be [primarily] a tree-climber, as claimed by some people," Haile-Selassie said.

The human-like physique supports other recent findings that suggest bipedalism was a very early development in the human lineage.

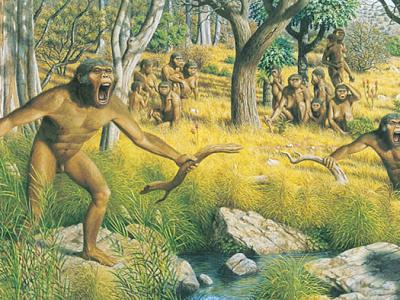

In 2009, for instance, scientists announced the discovery of Ardipithecus ramidus, or "Ardi," a 4.4-million-year-old female that some scientists think was an ancestor of A. afarensis.

Ardi's skeleton revealed she could already walk—albeit clumsily—on the ground and probably spent only part of her time in trees. (See Ardi pictures.)

Newfound Skeleton a Better Walker

Kadanuumuu's skeleton suggests A. afarensis was even less of a tree-dweller and a better walker than Ardi.

Ardi "was becoming a biped, but it truly had a foot in the trees," said Ardi co-discoverer Scott Simpson, a paleoanthropologist at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio.

The new A. afarensis fossil shows "that by the time we get to A. afarensis, we might still be in the trees. But the things we do on the ground are so crucial to our reproductive success that we've reorganized our entire musculoskeletal system to become a terrestrial biped," said Simpson, who was not part of the new study.

For example, in Kadanuumuu, certain leg muscles appear to attach to the pelvis in the same way as in humans. This would have helped the A. afarensis male balance on one foot, a necessary skill for human-like walking.

"This individual could actually stand on one leg and keep its balance. This is something chimpanzees cannot do," said Haile-Selassie, whose research appears this week in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

New Skeleton Not a Lucy Relative?

Zeresenay Alemseged, an anthropologist at the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco, disagrees.

Alemseged discovered the 3.3-million-year-old A. afarensis infant, Selam, which—although not a direct offspring—has been nicknamed Lucy's baby. (See pictures of Lucy's baby.)

The shoulder bone of that child was more gorilla-like than human-like, Alemseged said, suggesting the species still spent a major part of its time in trees.

A tree-dwelling lifestyle would have been useful to early species of Australopithecines, including A. afarensis, for nesting and evading predators, Alemseged said.

Alemseged also questions whether the new fossil indeed belongs to A. afarensis.

"With all cranial and dental elements missing, there is no compelling evidence to attribute it A. afarensis and not to other known species from around the same time, including Kenyanthropus platyops and A. anamensis," he said.

Kadanuumuu does not have preserved skull fragments or teeth, which are key to making a positive species identification, he said.