"Drilling Up" -- Some Look to Space for Energy

NASA has been looking into space-based solar power generation since the 1960s, the Associated Press reports.

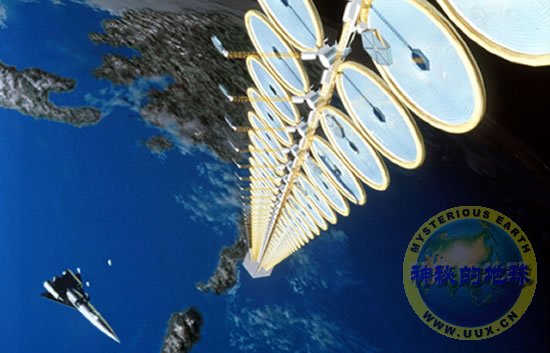

The space agency released this SunTower image in 1999, estimating back then that two small panels on a tall tower like this could power a communications satellite, and four panels might fuel a robotic interplanetary probe.

The Pentagon recently released a 75-page report on space power, and the president of the tiny Pacific country of Palau may end up handing over a deserted island to the cause.

Photo courtesy NASA

Charles J. Hanley in Bali, Indonesia

Associated Press

December 26, 2007

While great nations fretted over coal and oil at the UN climate conference in Bali, Indonesia, this month, one of the smallest countries there was looking toward the heavens.

The annual meeting's corridors can be a sounding board for unlikely "solutions" to climate change—such as filling the skies with soot to block the sun and cultivating oceans of seaweed to absorb the atmosphere's heat-trapping carbon dioxide.

Unlike other ideas, however, one this year had an influential backer—the Pentagon. The U.S. military is investigating whether space-based solar power—beaming energy down from satellites—could provide "affordable, clean, safe, reliable, sustainable, and expandable energy for mankind."

Tommy Remengesau Jr. is interested, too. "We'd like to look at it," said the president of the tiny western Pacific nation of Palau.

Palau and the Pentagon

The U.S. Defense Department in October quietly issued a 75-page study conducted for its National Security Space Office concluding that space power—the collection of energy by vast arrays of solar panels aboard mammoth satellites—offers a potential energy source for U.S. military operations.

In September, American entrepreneur Kevin Reed proposed at the 58th International Astronautical Congress in Hyderabad, India, that Palau's uninhabited Helen Island would be an ideal spot for a small demonstration. A 260-foot-diameter (80-meter-diameter) "rectifying antenna," or rectenna, could be set up to receive 1 megawatt of power transmitted to Earth by a satellite orbiting 300 miles (480 kilometers) above, Reed said.

That's enough electricity to power a thousand homes, but on an empty island the project would "be intended to show its safety for everywhere else," Reed said in a telephone interview from California.

Reed said he expects his U.S.-Swiss-German consortium to begin manufacturing the necessary ultralight solar panels within two years and to attract financial support from manufacturers wanting to show how their technology—launch vehicles, satellites, transmission technology—could make such a system work.

Reed estimates the project would cost about 800 million U.S. dollars and that it could be completed as early as 2012.

At the UN climate conference here this month, a partner of Reed discussed the idea with the Palauans, who Reed said could benefit from beamed-down energy if the project is expanded to populated areas.

"We are keen on alternative energy," Palau's Remengesau said. "And if this is something that can benefit Palau, I'm sure we'd like to look at it."

Solar Power Concentrate

Space power has been explored since the 1960s by NASA and the Japanese and European space agencies, based on the fundamental fact that solar energy is eight times more powerful in outer space than it is after passing through Earth's atmosphere.

The energy captured by space-based photovoltaic arrays could be converted into microwaves for transmission to Earth, where the rectennas would transform it into direct-current electricity.

Low-orbiting satellites, as proposed for Palau, would pass over a target area once every 90 minutes or so, taking about five minutes to transmit energy to be stored in batteries or used immediately. Electric cars, for example, could take such a charge via built-in rectennas.

This proposal differs from many other space-power studies, which focus on geostationary satellites that would orbit 22,300 miles (36,000 kilometers) above the Earth and remain over a single location to transmit a continuous flow of power.

The scale of that vision is enormous: One NASA study visualized solar-panel arrays three by six miles (five by ten kilometers) in size, transmitting power to similarly sized rectennas on Earth.

Each such mega-orbiter might produce five gigawatts of power, more than twice the output of a Hoover Dam.

Patrick Collins of Japan's Azabu University, who participated in Japanese government studies of space power, said a lower-power beam, because of its breadth, might be no more powerful than the energy emanating from a microwave oven's door, whereas the beams from giant satellites would likely require precautionary no-go zones for aircraft and people on the ground.

Space Energy's Potential

Rising oil costs and fears of global warming will lead more people to look seriously at space power, boosters believe.

"The climate change implications are pretty clear. You can get basically unlimited carbon-free power from this," said Mark Hopkins, senior vice president of the National Space Society in Washington.

"You just have to find a way to make it cost-effective."

Advocates say the U.S. and other governments must invest in developing lower-cost space-launch vehicles. "It is imperative that this work for `drilling up' vs. drilling down for energy security begins immediately," concludes October's Pentagon report.

Some seem to hear the call. The European Space Agency has scheduled a conference on space-based solar power for next February 29. Space Island Group, another entrepreneurial U.S. endeavor, reports "very positive" discussions with a European utility and the Indian government about buying future power from satellite systems.

To Robert N. Schock, an expert on the UN's Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, space power doesn't look like science fiction.

The panel's 2007 reports didn't address space power's potential, Schock explained, because his team's time horizon didn't extend beyond 2030. But, he said, "I wouldn't be surprised at the beginning of the next century to see significant power utilized on Earth from space—and maybe sooner."

Copyright 2007 Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed.