Meteor Caused Jupiter Flash, Hubble Reveals

Hubble findings suggest that a flash seen on Jupiter was caused by a meteor, not an asteroid or comet.

Andrew Fazekas

for National Geographic News

Published June 17, 2010

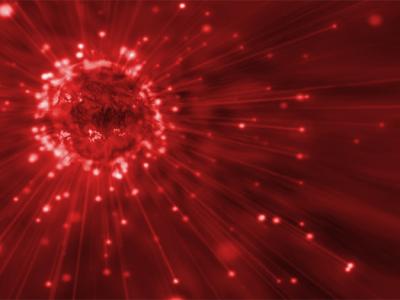

A mysterious flash of light seen on Jupiter early this month was likely caused by the disintegration of a meteor in the planet's upper atmosphere, Hubble Space Telescope images show. Astronomers had originally speculated that the culprit was a much larger asteroid or comet.

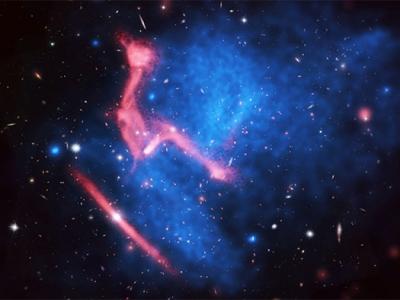

The Hubble found no trace of a dark debris field following the distinctive burst, which appeared for two seconds on June 3 and was spotted separately in videos taken by amateur astronomers Anthony Wesley of Australia and Christopher Go of the Philippines.

Astronomers suspected that a large meteor or comet had hit the gas giant, based on the fact that the Earth-size fireball was visible through backyard telescopes more than 470 million miles (770 million kilometers) away.

To investigate the size of the impact, Hubble's ultraviolet and visible-wavelength cameras were called into action three days after the blast. However, they found no telltale black smudges, such as those seen after a 1,640-foot-wide (500-meter-wide) asteroid had struck Jupiter in July 2009.

As a result, astronomers now speculate that a relatively small meteor burned up completely in Jupiter's upper cloud deck, similar to what happens when fireballs are seen on Earth.

"The lack of debris field tells us it was much smaller than the one that impacted last year, and that one was likely a few hundred meters," said Amy Simon-Miller, Hubble team member and chief of the Planetary Systems Laboratory at NASA's Goddard Spaceflight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. "Small ones would just vaporize in a flash; big ones penetrate to deeper pressures, where they explode, leaving a burned atmosphere to fall out."

Monthly Meteor Strikes?

Simon-Miller and her team think this weak strike may help in understanding the overall frequency of impacts with Jupiter. Based on the timing of the two recent blasts, the planet may get walloped as often as every few weeks.

Now it's just a matter of training telescopes on Jupiter and watching and waiting for the next light show. This is where backyard astronomers can really help, she said.

"Time on major observatories and Hubble are oversubscribed by ten to one, so we [professionals] can only get brief snapshots but can't monitor long-term," Simon-Miller said. "So amateurs should observe, absolutely. They are an invaluable resource to us."